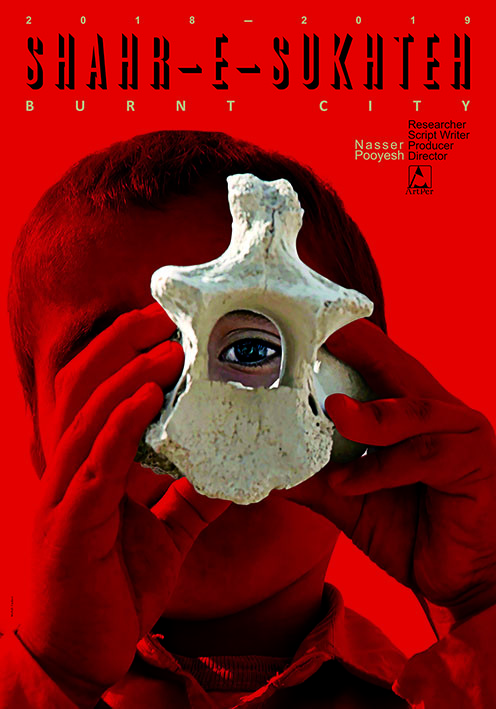

Director Biography – Nasser Pooyesh

From 1990, Naser Pouyesh began his activities in media as a film critic and chief editor. Then he worked as a director assistant for a short time. He produced 150 documentaries on archeology.

Referring to the film, Nasser Pooyesh, the director and producer said: “The interesting thing for me about Shahr-e-Sukhte was how a civilization survived for 1400 years without fortification, weapons and war, while no civilization has lasted this long throughout history.” He continued: “We know here was no central government or leadership in Shahr-e-Sukhte. The government was administered by a group which was matriarchal, meaning that power was in the hands of women. It may be for this reason that we witness no trace of violence and war in this city.”

He believes that this film is not archeological at all. Archeology is the beginning of the passage from reality to the truth.

The famous director of Hollywood’s statement about The Burnt City:

The Burnt City documentary is produced very beautiful. It is so important historically and all people will be attracted by watching it.

A look at the Docu-drama Film on Shahr-e-Sukhteh by Nasser Pooyesh

The footprint of people from beyond history

Alireza Behnam

Translation: Mojtaba Ahmad KhanThe civilization of Iranshahr is no short of secrets. The entire plateau of Iran is covered with mounds, which hold many ancient tales in their bosom. The Shahr-e-Sukhteh civilization to the south of Sistan and Baluchistan holds one of the oldest secrets of this ancient territory.

The Shahr-e-Sukhteh documentary film is an attempt to approach this mysterious past and to unfold the first known urbanization located today in the southeastern parts of the country. As a research documentary the film has a good opening. The images of surveys on an ancient mound with a cut in of explanations by Iranian and foreign researchers at the beginning of the film creates the ideal setting for questions. Based on the explanations of Dr. Sajjadi, the Head of Survey Team, we understand that relics of earthenware and skeletons of people living six thousand years ago have been discovered while an Italian archeologist interprets the findings and proposes theories on their mode of living. The attraction of this part of the film is in that both reports are presented in parallel, and there is no attempt by the director to highlight any part of these explanations. However, as the film progresses, his imagination seems to take him from realities and evidences to recreate the life of people, of whom our knowledge is truly “negligible”. In using his imagination in this reconstruction he goes to such extent as to create a language and to accompany the sentences told in this fictional dialect with subtitles. Furthermore, with an eye on the burial ceremonies and terracotta vessels left behind from this mysterious civilization, his imagination guides him to restore the scenes in a setting that recall the desert villages. It is at this junction that following the course of excavations is pushed to the background and the director’s vision in portraying the lives of people six thousand years ago becomes the focus of narration.

Andre Breton among the first theoreticians of Avant-garde cinema believed that re-enactment of reality was the greatest mission of a documentary film. In an article, Breton wrote: “The best documentaries are the analytical ones. It means they show an angle of the reality that is not dealt with as an observable truth. Instead, it is perceived as a social and historical truth, that can only generate reactions in a weave of energies. Secondly, these documentaries that are produced have no claim whatsoever to exactitude, but form their subject actively on the basis of structure, organization and their point of view. So, it is important to note that documentaries are made like any other feature film. They may not be considered are the record of reality, but they are another form of representing it.”

On this basis, we may consider Shahr-e-Sukhteh as an attempt to represent a reality, from which over long bygone years, we have received pieces, and have no choice but to stick them together with the glue of our imagination to perceive a vision of what has come to pass in this place on earth.

This may well be the reason why Pooyeh avoids highlighting the brilliant archeologic discoveries of Shahr-e-Sukhteh and passes them over with just a mention of the animation design on the urn discovered in the region. He even turns the artificial prosthesis eye discovered in a crypt in Shahr-e-Sukhteh into a secondary theme in the film’s chronicle, meaning that the girl, who used the prosthesis six thousand years ago, takes precedence over the scientific importance of the discovered object.

Thus, instead of merely reporting the archeologic surveys, the Shahr-e-Sukhteh documentary seeks a reality, which in the words of Breton are the “social and historical truths”. The interesting note in this reconstruction of reality is that in the course of this work, Pooyesh takes the opposite direction of the mainstream documentary film makers. Instead of shaping the main story around a true or imaginary hero, such as a researcher or even an imaginary ancient personality, he chooses to highlight the society and the social life, which is a difficult and a risky endeavour. The nameless woman-shaman or ailing girl in the film are as important as the contemporary local children, who pass and play along the archeologic trenches. In fact, in this manner, the six thousand-year history of this region of the world becomes the living history of its people.

Time out of joint

The Burnt City by Nasser Pooyesh

Luca Bandirali (University of Salento)

Torchlight illuminates a timeless night. A ritual is taking place. The camera records what is happening in the present tense, but which present are we talking about? Nasser Pooyesh’s film transports the viewer to a dimension where time is “out of joint”, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet puts it. The ritual exists in front of us, on the screen, in full view. But this ritual has the breath of the universe, outside human time. In relation to the rite we can be simultaneously far and near. Distant as in the long shots, which vibrate like the bright points of the flashlights. Close as in the chanting that accompanies the progress of the people with flashlights. For Nasser Pooyesh’s gaze, distance is important, because it allows us to capture the geometry of ritual. When the people’s path becomes circular, we understand the profound meaning of the film’s time: the event takes place now, in front of us, and at the same time it has taken place countless times in front of other eyes that we do not know. Our position as spectators is a privilege. We understand this from the first, startling overhead shot of the body stretched out and covered. Only the camera can offer us this vantage point. The face of the woman who accompanies the corpse’s journey to the afterlife appears and disappears, between darkness and light: in this luminous vibration, in this seeing and not seeing, there is the mystery of the ritual, something unrepresentable that the film aspires (and succeeds) in representing. The shot from above returns to construct the geometry of the circle (the shape of the bowl, cup and plate arranged progressively next to the corpse): if time is out of joint, the film consists of pure space.

The space of ritual in the film, however, is framed, as a spatialized image on the screen; of this image we are interested in the plastic elements (light, color, focus, composition) alongside the figurative ones. The space of plastic elements is a primary space, in which the viewer experiences his or her own implication; in this sense, the ontological difference between screen space and real space lies in the fact that in real space we are always and constantly included and implicated, while the film, by projecting the first image on the screen, makes space appear. The plastic elements of the frame concur to create what Antoine Gaudin calls “a kinaesthetic implication of the viewer in a vibrant volume of void”. The screen is thus the support of spatial composition, capable, for example, of producing alternations of solids and voids, or color variations. Accepting Gaudin’s hypothesis, we must assume the space on the screen as independent of the figurative elements of the image, including the habitability of the represented space. In essence, on the screen we see forms succeeding each other, and cinematic space is the totality of these forms, but also the concatenation that governs the succession of the forms themselves. The fundamental principle that gives rise to the dynamic space of film is the alternation between contraction and expansion. Of this principle, Nasser Pooyesh’s film is a crystalline enunciation.

This timeless space, this pure space, is the object of investigation of archaeology. The archaeological gesture is represented in the film by means of an “impossible” shot, a shot from the bottom to the top, from the deep ground to the sky. It is the timeless world observing the present. It is a bright present, a present dazzled by the light of broad daylight. On this bright contrast is built the structure of the film. The space of the ancestors and the space of the present. Even in this second space, the long shot is indicative of a strategy of distance and geometry. The beauty of the panning movement that captures the figures in long shot, while giving maximum emphasis to the ground, to the materic elements: this is the approach of the camera that proposes to us a fusion between the human and the space. It is the subjective shot of the children, the true centerpiece of Iranian cinema: a gaze that does not yet know the sedimentation of time, a pure gaze because it is removed from the causal chain of events, an unchained gaze. And again, the ability to set up a tension between what in focus and out of focus, a transitory, enigmatic state that renders the complexity of the real. The figure can or cannot be blurred and so the environment: the space that becomes place is what is most important. I would like to call this spatial attitude “ecosophy,” a unifying attitude, of fusion between man and nature, subject and object. The world itself coincides with nature, because physis is the totality of everything that exists, including the human world, thus one big system that includes humans and their many activities but also animals and plants, rivers, seas, the earth, the sky, the stars, and all the things that we can observe or with which we can somehow come into contact.

In this sense, The Burnt City expands the documentary form toward a broader form, which we can call “spatial imagination”, meaning by imagination, with Pietro Montani, that level of “original intermediation between something that is given and something that makes sense”. Film is, as a medium, one of the possible imaginative forms of this space or gap or interval that lies between the given and the meaningful. The cinematic imagination is spatial not only because it fills a space, but also and especially because it transforms the spatial fact, setting up the transition from a primary reality (the space of life) to a secondary reality (the framed space). The Burnt City is a film that knows how to move between the first and the second space: this is its strength, this is its beauty out of time.

Luca Bandirali is a researcher in Cinema, Photography and Television at University of Salento (Italy). His research interests include film aesthetics, history and geography.